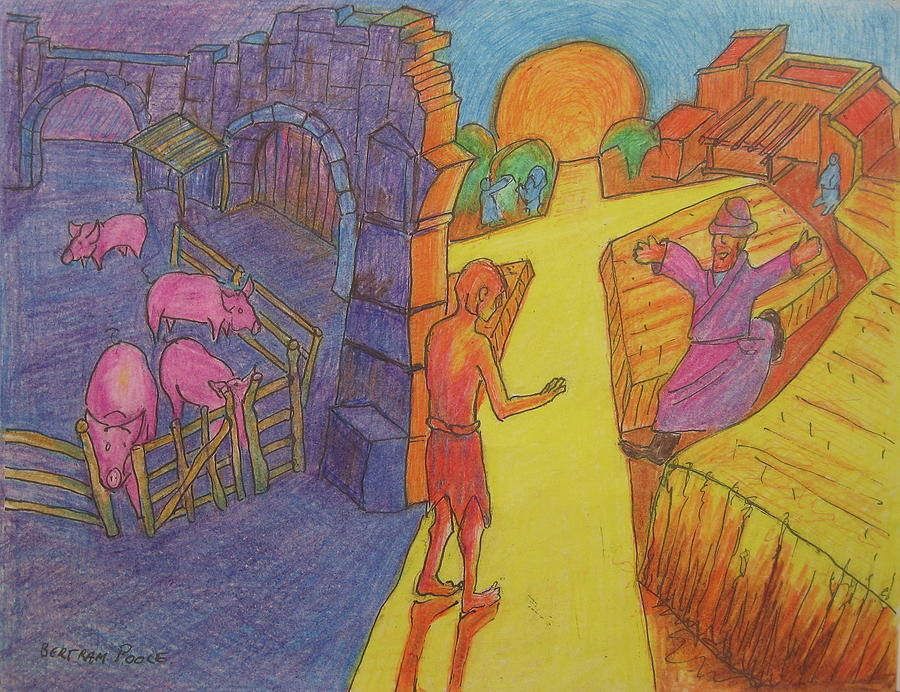

Prodigal Son Parable, by Thomas Bertram Poole

Introduction

Per my fourth commitment, I believe in a God who is primarily loving, gracious, and inclusive and only secondarily wrathful.

I believe that God is just and will punish persistent, unrepentant evil. But I believe his judgment is finite, fair, and ideally meant to lead to restoration. I believe that love and forgiveness reflect God’s dominate nature and first impulse. I believe that God seeks out relationships with people and to transform them into his way of love. I believe he has a plan to make right all that is wrong in the world. As an inclusivist, I believe that God relates to people from a variety of religions (and even people of no religion) based on what they do with the light that they have, such as it is. However, as a Christian, I believe that God has most fully revealed himself and most fully acted to save us in the person of Jesus.

Personal and Evidential Reasons

I believe in this sort of God for a number of reasons. I believe I have personally experienced God’s love, grace, and mercy in powerful ways. I have observed what appears to be his inclusive work in a variety of settings. Trust in and connection to this God grounds all of my other beliefs (including my commitments to truth, love, and justice). It inspires and justifies my overall orientation to the world.

But I don’t just believe in a primarily loving God because of personal experience. As I’ve studied religious experience more generally, it seems that most putative experiences of the Ultimate are of an overwhelmingly loving, good, blissful, or beautiful seeming Reality. These kinds of transformative experiences are reported by people throughout history and across the religious spectrum. Such experiences include a sense of mystical union, grace and forgiveness, transcendent beauty in nature, ecstatic worship, moral and spiritual transformation, and more generic feelings of peace and Presence. Even holy awe and (genuine) conviction of sin are compatible with God’s overarching benevolence; although from any perspective harmful beliefs about God can instill an oppressive and unwarranted sense of terror or shame.

As I’ve studied miracles, it seems that most of the best evidenced miracles are ones of healing and providential provision. These kinds of miracles obviously heal an infirmity or provide a need for the individual(s) they are given to. But they also tend to restore a stigmatized person to full fellowship with his or her community. They act as signs of God’s presence and concern for the suffering of his creatures. They are often an occasion of communal rejoicing and renewed hope. Although such miracles do not always happen, this phenomenon seems to show a caring and good God. By contrast, supposed miracles of harm are often undermined by scientific/archeological evidence and lack analogy to our current experience.

As I’ve studied universal moral norms, it seems that most of them are ones such as love, compassion, honestly, fidelity, and harm reduction. To the extent these norms reflect God’s own nature, as many theists believe, and not just his arbitrary will, they indicate a God of essential love and goodness. Further, many spiritual traditions see moral and spiritual transformation as organically linked to imitating the Divine and/or becoming uniting to It. If God’s character is fundamentally different than our own ethical ideals, this severs the organic linkage between virtue and imitating and uniting to God. We become something different than God simply because he is said to demand it, not because of anything intrinsicly spiritual, life-giving, holy, or god-like in that way of living. This does not fit the Christian experience or that of many other spiritual traditions. It also opens a dangerous door to abhorant deeds being justified as God’s arbitrary will.

As I’ve studied the world religions, it seems that doctrinally, most teach that the Ultimate (however they may understand it) is primarily loving, good, blissful, or beautiful. Christianity certainly teaches this, as I will suggest below. This is not to say that all religions are true or teach the same thing about the Divine. They do not. Nor is it to deny that many might also see a harsh and/or wrathful side to God – in some cases even attributing things to him that I would not agree with. But most would see God’s love, goodness, bliss, or beauty as being more dominant than his harshness.

There are pragmatic arguments for presuming that, all things being equal, God is good in an analogous way to what goodness elsewhere means to us. Analogously good views of God and his will lead to to human happiness, connectedness, and well-being; whereas harsh or violent views of God and his will lead to fear, conflict, and ill-health. Additionally, if God’s “goodness” can mean something different than what we everywhere else mean by that term, we end up with a God we cannot really trust or adore, we have no firm basis for ruling out heinous deeds as possibly being commanded by God, and theism’s typical grounding of human morality in God’s nature is fatally undermined.

There is also indirect support for a loving and good view of God in the form of arguments against opposing views that emphasize God’s harshness or violence. For example, as I have argued in detail elsewhere, we don’t tend to see unambiguous miracles of violent judgment by God today. Many miracles of violent judgment in the Bible are also undermined by evidence. Scientific and moral problems with the fall/curse narrative suggest that we are not guilty for Adam’s sin, nor is hardship in nature a punishment from God. Archeological problems with the conquest narratives as well as wider moral reflection indicate that God never calls us to indiscriminate violence (genocide) as his punishers. Evidential and theological considerations imply that unfortunate circumstances are rarely punishments from God. And we have good Biblical and rational reasons for rejecting an eternal conscious torment view of hell.

These insights have profound implications. Most vivid actual experiences of God or the Ultimate seem profoundly good. Ideas about God that seem bad are either based on dogma, debateable intuitions, or mythic history that is often disconfirmed.

Biblical Reasons

I believe the Bible itself also teaches that God is primarily loving and forgiving and only secondarily wrathful. Before proceeding, its important to note that the Bible also has violent images of God that I would not always agree with. Further, some of its loving images of God contain problematic elements. So my survey here is not meant to signal my full agreement with every such picture. But it does seems to me that even under a fairly conservative reading, the Bible too supports the notion that God is primarily loving and only secondarily wrathful.

Old Testament Theology of God’s Love

For example, according to the Old Testament God originally created the world as very good. Unlike in some other Ancient Near Eastern creation stories, God in Genesis does not create using violence. Creation is described as originally idyllic and lacking predatory killing and death (until the fall). Human beings are said to be created in God’s imagine, thus equally sharing in the dignity and task of imaging God in their benevolent rule over the earth. A number of passages indicate that God cares about this world, that he cares about human and even animal well-being.

After humanity’s fall into evil and banishment from the Garden, God is presented as seeking out covenant relationships with individuals and peoples. The Old Testament declares that God chose to enter into a covenantal relationship with Israel as his specially chosen people out of his love and mercy for them and with the ultimate purpose of blessing other nations as well. Many passages and metaphors testify to God’s passionate love for his people. God’s heart of love, mercy, and faithfulness is illustrated by the overarching narrative of his dealings with Israel; even where the language of love is not explicitly used.

Israel’s central confession about this God declares him to be a God who is compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness, maintaining his covenant of love to a thousand generations, and forgiving their sin; but by no means leaving the guilty unpunished. Variations of this declaration are repeated a number of times in the Pentateuch and are then quoted or alluded to in dozens of other places throughout the Hebrew Bible. In all versions, even arguably problematic ones, the contrast of God’s mercy with his judgment is disproportionately skewed towards love, mercy, and faithfulness. And most references to the confession omit the clause on judgment altogether.

Numerous times in the Psalms and elsewhere God’s love is said to endure forever. Many passages contrast God’s limited judgment with his abundant or even infinite love and mercy. Other passages indicate that God does not take pleasure in judgement, that promised judgment can often be averted if people repent of sin, and that God’s judgment is ideally meant to lead to restoration. And although some passages are xenophobic toward non-Jewish peoples, many others show God’s love for people of other nations and his eschatological plans to save and restore them, along with Israel and his entire creation.

New Testament Theology of God’s Love

Turning to the New Testament, Jesus and the early Christians believed that God was a loving and merciful Father who had sent his Son Jesus to liberate and restore his people, consummate his reign of love and justice, and make right all that was wrong in his creation. They believed that this Divine movement – what Jesus referred to as “the kingdom of God” – was breaking into the world in a climactic way through Jesus’ ministry, but it awaited its future full consummation. Below I will survey a few prominent New Testament themes regarding God’s love, looking first at its teachings about God the Father, then Jesus, and finally the Holy Spirit.

God the Father

The New Testament teaches that God the Father is merciful, gracious, and forgiving. For example, we see this in Jesus’ words that we are children of the Father if we extend forgiveness to others in the same way that God extends mercy to everyone; in his teaching that God justifies humble-penitent sinners over self-righteous Pharisees; and in his depiction of God as a compassionate father who runs to forgive his rebellious son. As I will note below, Jesus embodies God the Father’s grace and mercy concretely in his acts of mercy, compassion, and forgiveness.

The rest of the New Testament also emphasizes God’s mercy, grace, and forgiveness. For example, Paul called God the Father of mercies who is rich in mercy and who extends mercy to all who will receive it. To Paul, even as humans are entrenched in evil and actively enemies of God, because of his great love for us, God sent Jesus to die for us so that we could be graciously forgiven and reconciled to God. 1 John claims that “God is love” and that he has definitively shown us his love by sending his Son Jesus to die for our sins; if we confess our sins, God is faithful and just to forgive us and cleanse us from all unrighteousness. 2 Peter states that God is not willing that any should perish but that all people would come to repentance. James indicates that in God’s economy, mercy is meant to triumph over judgment.

Jesus and the other New Testament authors also teach that God the Father cares about the daily needs of his children and promises to provide them when we ask for them in faith. For example, Jesus taught that God provided for the birds of the air and lilies of the field and cared even more for the needs of his (human) children. He said that if human fathers give good gifts to their children, how much more will God give good gifts to those who ask for them in faith. And in the Lord’s Prayer he taught his followers to pray: “Give us this day our daily bread.” The other New Testament authors echo this view of God’s sovereign care. For example, Paul wrote that believers should be anxious about nothing but by prayer and petition present their requests before God. And 1 Peter tells us to cast all our anxieties on God because he cares for us.

Such teaching presents a dilemma, for many faithful-petitioning followers of Jesus do not receive even the necessary things for which they ask God. Was Jesus wrong? While I cannot address this issue in full, I will note that there is a tension in Jesus’ teaching between belief in a generously providing God whose Jubilee power is breaking into the world in new ways, on the one hand, and his belief that this present world/age is full of corruption, evil, and tribulation, on the other. Thus, although Jesus believed God often did provide for our basic needs in this life – that he really did care – and, this being the case, that it was appropriate to pray for them with confident expectation; paradoxically, he also recognized that the full redress of our needs/wrongs awaited an eschatological resolution when God’s kingdom was fully consummated.

Of course, tying together with all that has been said to this point, Jesus’ teaching about what God promises to do in the coming kingdom of God shows his great love for humanity, and indeed for his whole creation. Such promises included the forgiveness of sins, peace with God, a new covenant and renewed hearts that are able to follow it, the gift of the Holy Spirit, the healing of infirmities, the overturning of systems of violence and oppression, the realization of lasting peace and justice, the defeat and expulsion of Satan and his demons, the restoration of Israel and the Gentile nations, resurrection in renewed bodies, judgment of the wicked and vindication of the righteous, reunion with lost loved ones, a renewed creation without suffering or death, and the chance to see God “face to face” (so to speak) and be with him forever. These things are manifestly good. Almost unbelievable so. They testify to God’s benevolent intentions for the world, whether the language of love is explicitly used or not. Similarly, many of God’s names and attributes imply his love, even when that lexical terminology is not used.

The New Testament teaches that, out of love, and before the world was even created, God had sovereignly chosen those “in Christ” to be his children and heirs to the priceless inheritance of salvation. It teaches that God is able to keep them from from falling away (so long as they persevere in faith), that nothing can separate them from the love of God. Some interpretations of this teaching imply a cruel and arbitrary God. However, it was probably originally meant as a source of encouragement and hope for believers. My study has led me to reject Calvinist views of predestination/election and adopt more benevolent Arminian ones.

The New Testament teaches that God the Father disciplines his children, whom he loves. In my view, many applications of this teaching are abusive, including some Biblical ones. However, it makes sense to me that a loving Parent would, in some way, discipline their children. It would be unloving to stand by while children engaged in behavior that was destructive (to themselves or others). A loving parent would want to use proactive means to encourage the maturity, morality, and well-being of their children. At the very least, I believe God convicts us of sin, empowers and guides our sanctification, and sometimes gives us over to harmful consequences of our sinful choices.

I believe that God’s final judgment can also be seen from the perspective of his love for victims of injustice. In this life, evil people sometimes seem to get away with the harm they do. Good-hearted people are sometimes trampled down, slandered, or simply passed over on account of their virtue. But God promises that someday everyone’s deeds will be revealed as they give an account for how they have lived and the true nature of things is exposed. And while God offers forgiveness and restoration for those who turn from evil, he warns of dire consequences for those who knowingly and persistly resist his way of love.

Many New Testament passages indicate a special love between God the Father and his unique son Jesus. These and other passages (including ones that connect the Holy Spirit with this divine dance of love), are the inchoate basis for the Christian doctrine of the Trinity. Christians believe that the one essence of God is made up of three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Love characterizes God’s nature and essence (“God is love”). God has always existed in eternal harmony in loving relationship between these co-equal members of the one God. Although God always bears all of God’s attributes within Godself, it would seem there is something special and primary about love. God in Trinity has been and always is expressing it. There was a time when God was not expressing his wrath (“before” there was anything but himself). But he has always been expressing his love.

Jesus

Moving on, Jesus is himself remembered as being an exceptionally loving, compassionate, and forgiving individual. A number of times the Gospels explicitly mention Jesus’ love for various individuals. In many other places Jesus is said to have compassion or mercy on strangers and on the crowds of people that came to him. Jesus seems to have shown particular love and compassion toward marginalized people who the religious and political elites saw as “nobodies.”

Such love and compassion can be seen in Jesus’ miracles. He is remembered in multiple accounts as healing people, including those afflicted with blindness, leprosy, epilepsy, physical deformities, lameness, and even raising people from the dead. Jesus is also remembered as exorcising evil spirits from demonized people. As noted in a prior post, such miracles did not just free such people of their physical or spiritual ailments, it allowed them to be restored again to communities that would have previously shunned them as “unclean” or cursed by God. Jesus’ other miracles also show his concern for the wholistic well-being of others. For example, his multiplying of food to feed hungry people or his calming a storm to save his disciples from peril. All of these miracles have a rich resonance with God’s saving acts in the Old Testament. Jesus saw them as instances of God’s kingdom breaking into the world and overturning Satan’s kingdom. Finally, it is noteworthy that Jesus only performed life-giving miracles, not miracles of violence or destruction (though he expected supernatural destruction in the eschaton).

Jesus’ love and compassion can be seen in his extension of God’s mercy, grace, and forgiveness to people. For example, Jesus is remembered as seeking out sinners, calling people to repentance, and sharing table fellowship with people perceived as sinners. Often when Jesus healed people he would also pronounce forgiveness of their sins. Jesus called his disciples to love their enemies, forgive those who wronged them, and forgo violent retaliation; and he himself modeled such actions. Jesus’ mercy, grace, and forgiveness were most dramatically revealed in the events surrounding his death. At that time, he rejected violence against those who wrongfully accosted him – even healing one of them in the process; from the cross he prayed for God to forgive his own crucifiers; and then, after his resurrection, he forgave the very disciples who had abandoned him. Of course, the early Christians saw the coming of Jesus, and particularly his death and resurrection, as God’s climactic act that would eradicate sin and its effects, thus enabling forgiveness and restoration.

Jesus’ love and compassion were also one of the main reasons he taught others about the kingdom of God. According to Mark, Jesus’ teaching was motivated by having compassion on the crowds after seeing that they were like sheep without a shepherd. Of course, Jesus’ message about God’s in-breaking kingdom was “good news” (at least for the poor, the penitent, and those who hungered for justice). Even Jesus’ warnings about the need to repent in light of God’s coming judgement were motivated out of genuine concern for others. Matthew and Luke remember Jesus weeping over Jerusalem, wishing he could gather its inhabitants under his protective wings (so to speak); but they largely spurned his message, and so, from his perspective, risked divine judgment. As I noted in my last post, Jesus saw love as the greatest commandment. And his aim was to build up an alternative community centered on love, scandalously, inclusively, open to all who would embrace his message.

Moving from Jesus as a mere human figure to a “high” Christological perspective that sees Jesus as God incarnate, in the New Testament Jesus is seen as embodying God’s love in his incarnational life, death, and resurrection.

From a New Testament perspective, Jesus is God the Son, the eternal Logos, humanity’s Messiah and Lord. Out of love for us, and in accord with his Father’s plan, he chose to leave the comfort and immediate intimacy with his Father in heaven and come down to earth to take on flesh as a human in order to save us. Even before considering Jesus’ torturous death on a cross, just the harshness of his life as a poor oppressed Jew is remarkable. Paul says that although Jesus was rich, for our sake he became poor. Although he was the King of Kings, he chose to be born into a poor family and sleep in a manger among animals rather then in a palace. He grew up in a far-flung province occupied by an oppressive imperial power. According to Matthew’s account, Jesus’ family had to flee for their lives from Herod and temporarily sojourn as refugees in Egypt. Hebrews says that he was tested in every way, without choosing to sin, and that he learned sympathy with our weakness and sorrows by his own incarnational suffering.

Turning to Jesus’ death, toward the end of his ministry Jesus chose to head toward Jerusalem to challenge this seat of power with his message concerning the kingdom of God. Many texts remember him as anticipating his likely death there and seeing a special significance behind it. In particular, he is remembered as seeing his death as the price paid (“ransom”) to free people, achieve forgiveness of sins, and inaugurate covenantal renewal. Jesus also believed that God would subsequently vindicate him by raising him from the dead.

While in Jerusalem, Jesus was arrested, wrongfully convicted, beaten and humiliated, and then nailed to a cross. Crucifixion was a shameful and torturous form of execution used by the Romans (and others) against those who resisted imperial rule. That it was used on Jesus, speaks to the subversive nature of his movement. That Jesus willingly submitted to it “for us” shows the incredibly sacrificial nature of his love.

Jesus’ death struck a terrible blow to his disciples. But the early Christians came to see Jesus’ death and (as they saw it) his subsequent resurrection as at the center of Gods saving action to make right all that was wrong in the world. To them, it had a surplus of meaning. Thus, the significance of Jesus’ death transcends easy capture in any one atonement theory. Further, while keeping early Christian reflection as our starting point, Christians from later times and places have continued to find new meaning behind Jesus’ death (while sometimes critiquing older understandings).

Some of the most important meanings the New Testament ascribe to Jesus’ death include the following: Jesus died being faithful to his perceived vocation as a prophet and in solidarity with the marginalized people for whom he advocated. He died to provide us an example to follow in how to live and love. He died to eradicate sin and its effects and definitively extend us God’s mercy and forgiveness. He died to reveal God’s true nature and stance of toward us. He died to defeat death and inaugurate renewed creation. He died to defeat the demonic Powers that deceive and oppress us. He died to achieve reconciliation: between God and humans, between Jews and Gentiles, between humans more generally, and with estranged creation. He died to to inaugurate a new covenant that would fulfill the intent behind Israel’s calling. Finally, the New Testament is clear that Jesus died for everyone and that God longs for all to be saved.

Holy Spirit

Moving on, in the Bible, the Holy Spirit is often associated with God’s creative power, his giving (and sometimes taking) of life, and his word(s). The Old Testament refers to God’s Spirit as a source for the eschatological restoration of God’s people and the world. In some passages this renewal is depicted either as the result of a direct outpouring of the Spirit upon the people or as the result of the ministry of the Spirit-annointed Messiah/Servant. The New Testament sees these things as fulfilled in Jesus’ Spirit-filled life and in the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on Jesus’ followers.

In the New Testament, the Holy Spirit is said to pour God’s love into our hearts. The Spirit is said to regenerate us, sanctify us, advocate for us, act as a comforter/counselor, help us pray, give us assurance that we are children of God, grant us good gifts and spiritual fruit, inspire and reveal God’s words, act as a down-payment and guarantee of our future reward, and many other benevolent things.

In all of these ways and others, the Bible shows that God is primarily loving and forgiving and only secondarily wrathful.

Legitimate Doubts

Before going on, I want to acknowledge that, in spite of all this, and despite my own belief in a loving God, there are legitimate reasons one might question the existence of such a God (or any God). There are a range of sophisticated arguments for and against God and a supposedly loving God, particularly, is vulnerable to counter-arguments related to the problems of evil and divine hiddenness (as well as other challenges). At times I’ve personally doubted the existence of a good God. It’s important to be honest about these complexed realities.

The Centrality of Grace

I want to say something more about the centrality of grace to my view of God. I’ve struggled over God’s mercy, grace, and forgiveness for a number of reasons. I come from a religious background where I was immersed in violent and punitive views of God, a depraved view of human nature, and a legalistic set of obligations. This often made me afraid of God and it played into unhealthy shame and a negative sense of self-worth. My own perfectionistic nature and complicated relationship with my (earthly) father also played into these things. While I now repudiate some of these views, my own moral intuitions suggest to me that we are all guilty of some wrong-doing, that God must be just, and that he must therefore hold us to account for our wrongdoing in some way. Both Christianity and many other religions teach that God is just and judges evil. Other religions, which do not believe in a personal God, teach that there are cosmic bad consequences for evil behavior. The Bible also teaches that God is just and judges evil. And while some passages imply that we are saved by sheer grace; other passages seem to imply that salvation is conditioned (in some way) on our good works. Finally, a “cheap grace” view of salvation, which shirks the need for costly change in learning to love others, strikes me as hollow and repugnant.

In spite of this, while I believe we are called to turn from evil and progressively be transformed to love as God does, God’s mercy, grace, and forgiveness are my bedrock starting points for a variety of reasons. First of all, this is based on my own dominating, vivid-seeming experiences of God’s mercy, grace, and forgiveness. These include specific religious experiences of these things as well as a more general sense of God’s unconditional love in my life. Coming to believe that God loves and accepts me, even where no one else does, no matter my starting point, if I genuinely repentant of my sins and trust in him, has healed and grown me in significant ways. My research into religious experience more generally suggests that divine forgiveness and receptivity are central to many others’ experiences of the Ultimate. As I have briefly argued, the Bible itself seems to teach that God is primarily merciful and forgiving and only secondarily wrathful. My study indicates to me that most other religions also see God as more merciful than wrathful. Finally, my research points to evidence that undercut many violent and punitive beliefs about God.

An Inclusive God

I’ve briefly touched on some of my reasons for believing that God is primarily loving and gracious, but what about the inclusive part? Why believe that God relates to humanity in a salvifically inclusive manner?

People from a number of different religions testify to vivid-seeming experiences of God (or the Ultimate) and evince profound moral and spiritual transformation. This counts as strong face-value evidence that God is at work in these various religions. There is ambiguity to the evidence for or against any one religion and there are evidently sincere practitioners of a number of different religions. God’s justice implies he would only hold people accountable for what they know and can do. But not everyone knows that any one religion is true. Thus, a just God would not judge people on the basis of whether they embraced the right religion in this life – even if there was one true religion – but only on what they do with the light they have, such as it is. God’s universal love and mercy imply that he would do everything he could to save everyone, that he would find creative ways of beckoning and meeting people from all times and places, even if we did not justly deserve this. Many of God’s other attributes such as his transcendence, spiritual nature, and power fit well with a more mysterious and “flexible” view of God and his interaction with people and the world. Pragmatically, exclusivist views of God and salvation lead to great harm toward others whereas inclusive views lead to loving and respectful treatment of others. And finally, although much of the Bible seems to take an exclusivist view of God and salvation, there is a significant minor stream of texts which arguably support a more inclusive view on these matters.

Conclusion

Because I believe God is primarily loving, gracious, and inclusive; because I believe God’s love and goodness have to be understood as analogous to what those terms elsewhere mean for us as humans; and because of rational and evidential problems with many specific harsh views of God and his will; I reject a number of problematic beliefs about God. For example, I reject Calvinism, an eternal-conscious-torment view of hell, that God ever stands behind human genocide (per Old Testament “texts of terror”) or systems of oppression such as slavery or patriarchy, and so on. I reject similar views in other religions as well. In some of these cases my study has also provided Biblical evidence against such harsh interpretations, or for more benevolent ones.