Introduction

In my last post of this series I argued that there is broad, interfaith consensus that the Ultimate is primarily loving, good, blissful, or beautiful. In today’s post I will turn to a range of pragmatic arguments for assuming that God is primarily loving based on how different concepts of God work and the differential effects they have on people.

I’ve argued that the phenomenological evidence strongly points toward God being loving. But say we didn’t have all that. Say we simply started out with different views of God, each initially just as plausible as the next. How might we proceed in the face of such uncertainty?

I contend that we should start out presuming that God is good in a way that is for us and analogous to what goodness elsewhere means to us, apart from strong evidence to the contrary. Views of God as predominately loving and as calling for us to reflect his love in our treatment of others should be presumptive.

Further, “love” should be assumed to be similar to our best notions of the word and our theology and ethics should be assumed to fit what we empirically know about the world. This view of God and his will should be our default baseline, apart from evidence to the contrary.

Pragmatics have to do with “what works best.” The truth is, different ideas about God and/or God’s will have demonstrably different effects on people. Some conceptions are generally more conducive to human happiness, connectedness, and well-being. Some tend to instigate fear, conflict, and ill-health.

Additionally, if God’s goodness can mean something different than what we everywhere else mean by that term—if arbitrariness, torture, genocide, and the like are really “good” when God is said to engage in them or command them—then calling them that involves equivocation, we end up with a God we cannot really trust or adore, we have no firm basis for ruling out heinous deeds as possibly being commanded by God, and theism’s typical grounding of human morality in God’s nature is fatally undermined.

Now, pragmatic considerations are not the only or even the most important ones. Truth and evidence are key. That is why I started there in this series.

However, we already saw that the evidence for a real physical world and this-worldly norms of love and justice are strong. We saw that in broad strokes, these realities are better evidenced than more debatable theological beliefs. In fact, I will argue in a later series that there is an element of ambiguity about what larger worldview is true.

This suggests to me that we should start out giving strong presumption to views of God and God’s will that fit with our physical and moral experience of the world and human flourishing. These should be our baseline assumptions, apart from evidence to the contrary.

If there were evidence to support a harsh view of God or God’s will, it would make sense to recognize that and act accordingly. But harmful, oppressive views need to bear the burden of proof. And in my view, this burden is both high and unmet.

As I said, I’ve presented positive evidence for thinking that God is predominately loving and for moral norms centered on love and justice. But apart from that, even if there ends up being no God, such a view is structured to make sense in this life; to bring good in this life, to ourselves or others. Views of God as primarily loving, gracious, and inclusive bring very good fruit and their opposites bring very bad fruit (as we will see).

Different Views of God Effect Physical and Psychological Health

Studies show that fearful, authoritarian views of God that prominently emphasize his anger or punitive wrath harm the brain, decreasing empathy toward others and our ability to use our rational facilities. By contrast, views of God that emphasize his love, compassion, and grace foster brain health and increase empathy and our ability to use our critical faculties. Psychiatrist Timothy Jennings observes the following:

Does it matter which God-concept we hold? Recent brain research by Dr. Newberg at the University of Pennsylvania has documented that all forms of contemplative meditation were associated with positive brain changes – but the greatest improvements occurred when participants meditated specifically on a God of love. Such meditation was associated with growth in the prefrontal cortex…and subsequent increased capacity for empathy, sympathy, compassion, and altruism. But here’s the most astonishing part. Not only does other-centered love increase when we worship a God of love, but sharp thinking and memory improves as well. In other words, worshiping a God of love actually stimulates the brain to heal and grow.

However, when we worship a god other than one of love – a being who is punitive, authoritarian, critical or distant – fear circuits are activated and, if not calmed, will result in chronic inflammation and damage to both brain and body (Jennings, 2013, p. 27).

Jennings goes on to give a fuller explanation of the kinds of damages that prolonged activation of the fear circuits in the amygdala can cause. These include increased risk of type 2 diabetes, obesity, elevated cholesterol and triglycerides, heart attacks, strokes, ulcers, infections and inflammatory disorders, decreased energy and motivation, impaired concentration, aches and pains, and sleep disturbances (Jennings, 2013, pp. 154-156).

Andrew Newberg, in the book Jennings cites, explains it this way:

Contemplative practices stimulate activity in the anterior cingulate, thus helping a person become more sensitive to the feelings of others. Indeed meditating on any form of love, including God’s love, appears to strengthen the same neurological circuits that allow us to feel compassion toward others.

In contrast, religious activities that focus on fear may damage the anterior cingulate, and when this happens, a person will often lose interest in other people’s concerns or act aggressively against them. We suspect that fear based religions may even create symptoms that mirror post-traumatic stress disorder. Brain-scan studies have shown that once you anticipate a future negative event, activity in the amygdala is turned up and activity in the anterior cingulate turned down. This generates higher levels of neuroticism and anxiety (Newberg and Waldman, 2009, p. 53).

Studies also show that loving, supportive views of God have a positive impact on health and healing. Harshly punitive views of God and medically unsound beliefs about his will can lead to physical and psychological harm or even death.

For example, in an article in The Cambridge Companion to Miracles, Niels Christian Hvidt surveys positive and negative coping resources that people can have in regard to medicine, prayer, and miraculous healing.

Negative coping resources include harmful beliefs such as the refusal of Jehovah’s Witnesses to accept blood transfusion or the “snake handling” practices of some Pentecostals (Hvidt in Twelftree, 2011, p. 317). They include people rejecting medical treatment because of the belief that they should trust in God’s miraculous healing as an alternative form of therapy capable of replacing medicine (Hvidt in Twelftree, 2011, p. 317). And they include demands of senseless extension of regular treatment in hope of a miracle (Hvidt in Twelftree, 2011, p. 318).

Positive coping resources include the hope and sense of relationship with God that trusting prayer can bring (Hvidt in Twelftree, 2011, p. 311). They include willingness to combine prayer for healing with proactive pursuit of medical treatment. And they include the ability to recognize and accept that God does not always heal (Hvidt in Twelftree, 2011, p. 322).

What I find most interesting for our purposes here is that different conceptions of God also have different effects on health outcomes in regard to sickness and healing. For example, the belief that God controls everything combined with the belief that God sends accidents, sickness, or suffering as punishment for misdeeds can lead to negative outcomes (Hvidt in Twelftree, 2011, pp. 315-316).

Alternatively, a view of God as loving, supportive, and as entering into the patient’s suffering with them can lead to positive health outcomes, as can a view of God as controlling all things when combined with the belief that he can bring good out of difficult situations (Hvidt in Twelftree, 2011, pp. 315, 319).

Hvich’s summary is worth quoting at length:

Research suggests that negative religious resources, such as belief in God as an agent of retribution, may augment the risk of cancer-related depression…Conceptions of God in which illness and crisis represent divine punishment have been shown to provoke stress and low self-esteem, whereas the opposite applies when patients believe that God enters into their suffering, bears it with them and supports them throughout the disease. The idea that God punishes through disease and traumas is, as Pragament’s research shows particularly clearly, considered an example of ‘negative religious coping.’ Such negative coping has been associated with a decrease in psychological functioning, quality of life and longevity (Hvidt in Twelftree, 2011, p. 315).

Bad Views of God Play Into Violence and Oppression

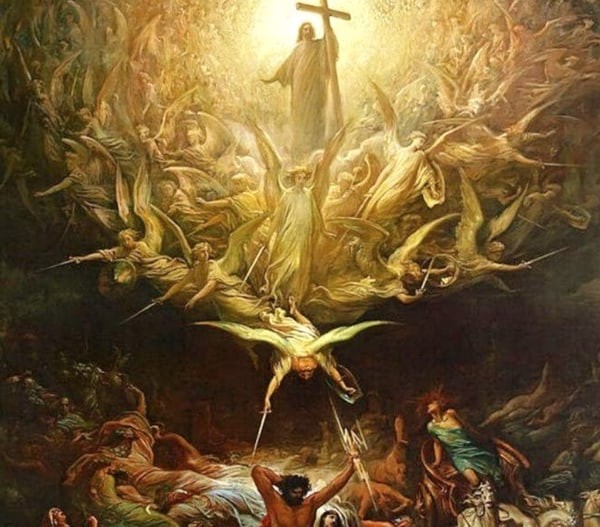

The belief that God is violent and domineering and can command violence and oppressive uses of power against others can lead to religiously justified violence and oppression. Such beliefs stir up fear and hatred. They inhibit dialogue, tolerance, and peace. They are used to justify heinously unloving and unjust behavior toward others.

I think this is especially the case when they are combined with a dualistic view of one’s in-group as opposed to other out-groups, imminent apocalyptic expectations of violent judgment, a sense of unique choseness or election, an exclusivist view of God and salvation, a rigid and oppressive interpretation of one’s religious tradition, and/or a perceived call to convert and/or dominate others. The issue is not just the specific harsh beliefs a group might have, it is also the prominence given to them within the system.

Examples of religious beliefs contributing to violence are numerous. They include the crusades, inquisition, various witch hunts, religiously inspired conflicts such as the Thirty Years War, conflict between Hindus and Muslims in East Asia, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the Middle East, religious justifications for colonial conquest, slavery, and genocide, Aztec and Ancient Near Eastern human sacrifice, Muslim conquests and violence against those perceived as infidels, religiously inspired terrorism and extremism, the use of Zen Buddhism to promote Japanese imperialism in the 1930s and 40s, and so on.

Religion has also often played a role in oppressive ideologies and systems that cause demonstrable harm to many. For example, religion has been used to justify racism, sexism, classism, slavery, homophobia and transphobia, economic exploitation and inequality, environmental degradation, and so on.

Its important to point out that violence and oppression are not just religious impulses. Tribalism, violence, and hierarchal structures of power are, to some extent, a part of our human (and even animal) nature (Pinker, 2011, pp. 31-58; de Waal in Oord, 2008, 242-262).

In her book Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence Karen Armstrong observes that,

The two world wars were not fought on account of religion. When they discuss the reasons people go to war, military historians acknowledge that many interrelated social, material, and ideological factors are involved, one of the chief being competition for scarce resources.(Armstrong, 2015, p. 4).

And as Tim Keller points out, religion is not the only type of ideology that has perpetrated violence.

The Communist Russian, Chinese, and Cambodian regimes of the twentieth century all rejected organized religion and belief in God. A forerunner of all these was the French Revolution, which rejected traditional religion for human reason. These societies were all rational and secular, yet each produced massive violence against its own people without the influence of religion. Why? Alistair McGrath points out that when the idea of God is gone, a society will “transcendentalize” something else (Keller, 2008, p. 55).

All of that to say that religion is not the only cause of violence and oppression and (as we will see) it does not inevitably lend itself to such things.

Good Views of God Promote Love, Peace, and Justice

On the other hand, views of God as predominately loving, gracious, peaceful, just, and inclusive (and calling for us to imitate such attitudes in our behavior toward others) lead to demonstrably good effects. They encourage open-minded, sympathetic engagement with others. They tend to promote love, peace, and justice in the world.

For example, an analogously good view of the Divine and its way played an integral role in the abolitionist movement in England and the United States, Gandhi’s non-violent actions for Indian independence from Britain, the Civil Rights movement in the United States, a peaceful end to apartheid in South Africa and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the efforts of various “Engaged Buddhists” for peace and justice, and so on.

In their book Religion, the Missing Dimension of Statecraft, Douglas Johnson and Cynthia Sampson give seven modern case studies of times when religion played an outsized role in enacting peace. Three case studies involved non-violent struggles that would have turned violent without church influence. Three involved ending wars that were already in progress. And one involved reconciliation after a major conflict ended (see the overview in Smith and Burr, 2007, pp. xl-xlii).

Many other sources survey examples of religious figures and movements that have worked to love others and advance peace and justice; and all of this specifically because of their religious experiences and teachings from within their religious traditions (see Smith and Burr, 2007; Hick, 1988, pp. 299-342; Witte and Green, 2012; Armstrong, 2006; etc.).

There are progressive religious movements that push for and seek to live out justice in regard to women, poor people, racial and ethnic minorities, immigrants, LGBTQ folk, religious minorities, people of all ages and abilities, and the environment.

As a final illustration of how analogously good views of God can lead to good effects toward others, in their book The Heart of Religion social science researchers Matthew T. Lee, Margaret M. Poloma, and Stephen G. Post document how perceived experiences of God’s love motivate and expand people’s benevolence toward others in statistically significant ways (Lee, Paloma, and Post, 2013, pp. 19-30). Here is one of their summaries:

Perhaps our single most important finding concerns the extent to which experiences of divine love are related to a life of benevolent service. For many Americans, the two are inseparable. And indeed, repeated experiences of divine love can provide energy for a “virtuous circle” in which a positive feedback loop fosters increasingly intense or effective acts of benevolence. This holds across religious and social groups. Whether liberal or conservative; male or female; young or old; black, white, or Latino; or Amish, Episcopal, or Pentecostal, powerful experiences of God’s love motivate, sustain, and expand benevolence (Lee, Paloma, and Post, 2013, p. 21).

The authors make clear that this is not only love towards family and friends, but also more extensive benevolence in caring for larger community and being a citizen in the world (Lee, Paloma, and Post, 2013, p. 51).

However, they do recognize that how love is exercised depends on one’s other beliefs and the interpretive grid through which they understand the world. Some belief systems will be more conducive to effectual love and justice than others (Lee, Paloma, and Post, 2013, pp. 189-222).

Finally, they make this fascinating observation:

Our work shows that emotionally powerful experiences are key, and they often reshape beliefs. Our interviewees generally moved in one direction: discarding a judgmental image of God picked up during childhood socialization in favor of a loving and accepting representation of God that is more consistent with their direct, personal, and affectively intense experience (Lee, Poloma, and Post, 2013, p. 21).

Critics of religion sometimes try to play down religion’s positive role in movements for peace and justice.

For example, Eric Reitan points out how Christopher Hitchens claimed that Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the Lutheran pastor who was executed for resisting the Nazis, was not truly motivated by religion, but by “an admirable but nebulous humanism” (Reitan, 2009, p. 18). And according to Hitchens, Martin Luther King Jr. was not “really” motivated by Christianity because he preached forgiveness of enemies and universal compassion rather than retributionism or hell (Reitan, 2009, p. 18).

Reitan goes on to cite direct passages from King’s writings that show he was profoundly shaped by his experience of God’s love. I cite an abbreviated portion here:

God has been profoundly real to me in recent years. In the midst of outer dangers I have felt an inner calm…I have felt the power of God transforming the fatigue of despair into the buoyancy of hope. I am convinced that the universe is under the control of a loving purpose, and that in the struggle for righteousness man has a cosmic companionship. Behind the harsh appearances of the world there is a benign power (quoted in Reitan, 2009, p. 42).

Clearly good conceptions of God and God’s will can lead to ethically good effects in the world.

A Matter of Great Urgency

Finally, I think we need to keep in mind how high the stakes are here in relation to different conceptions of God and his will. I remember something Brian McLaren wrote on this matter:

In the twenty-first century, Christianity – along with all world religions – must develop a more mature, robust, and ethically responsible theology of violence and peacemaking. It was one thing for our ancestors to use God’s name to legitimize violence inflicted with swords and spears; it was another thing when more recent ancestors sought to justify violence with guns and artillery. But for us and our children, living in a world of nuclear bombs, biological and chemical weapons, and as-yet unimagined terrorist adaptations of these weapons of mass destruction; the issue of God and violence takes on unprecedented importance (McLarin in Hardin, 2013, p. xiv).

One could say the same thing about different beliefs about God and the world in regard to challenges such as climate change and systemic injustice.

Some Other Religious Beliefs and Their Practical Effects

In later posts I will survey a number of bad effects that can come from belief in imminent apocalyptic destruction. For example, these include superstitious misreadings of people and events, sanctified violence, and opposing efforts to work for peace, justice, and planet care. I will also argue that an eternal conscious torment view of hell has caused enormous fear, despair, and violence toward others.

However, I will also argue that a better view of God’s eschatological judgment is available and it can lead to good effects in the world.

In another series of posts I will also argue that exclusivist views of God and salvation tend to lead to bad fruit. For example, they play into anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, and oppressive colonialist stances toward indigenous peoples. They often play into ignorant and false views of non-religious people and people in other religions.

But an inclusive view of God and salvation can lead to open-minded dialogue with others, mutual respect, ecumenical engagement on shared goals and values, and more fair and honest discourse about people of other faiths or of no faith.

A Good God Creates Harmony Between God’s Good Nature and Human Goodness

As I’ve already contended in my fourth post in this series, an analogously good view of God creates harmony between the God we imitate and are united to and the moral character we are expected to be transformed into. In that post I argued that this is the way believers tend to experience both God and moral transformation.

Here I am arguing that this way of conceiving God and morality bears a parsimonious simplicity, leads to good fruit, and cuts off a possible justification for heinous deeds at the roots. As I argued in that fourth post, we become like what we worship. Thus, what we think about God (or the Ultimate) is one of the most important things about us. Because of this, it makes sense to start out presuming that God and is analogously good, unless we have a good reason to think otherwise.

Non-Analogous Understandings of God’s Goodness Lead to Equivocation

In their book Good God, philosophers David Baggett and Jerry Walls argue that God’s goodness must have some recognizable similarity to our common notions of goodness and morality or his “goodness” becomes meaningless and we are left with a practical (theological) volunteerism where any alleged commands of God, no matter how abhorrent, could actually be “good” and reflect his good nature. Further, if God’s “goodness” is like this, we have no firm basis to trust him.

Baggett and Walls recognize that we are finite and sinful and that sometimes God’s actions or commands might seem problematic but actually be good. But they also believe some things have to be outside the bounds of what we would expect a good God to do. Because of this, they distinguish between what is difficult to reconcile with our moral intuitions and what is impossible to do so. They recognize that we might not be able to fully demarcate a line. They see torturing little children for fun as one thing that would fall into the impossible realm. There is no way a meaningfully good God could command such an action (Baggett and Walls, 2011, pp. 125-136).

Interestingly, they also argue that Calvinism falls into the impossible realm. This because the priority it assigns to God’s will leads to either ontological or practical volunteerism and its teachings on election imply that countless persons will be consigned to an eternity of utter misery as punishment for the very choices God unconditionally determined them to make (Baggett and Walls, 2011, pp. 65-81).

I note in passing that equivocation and making God into a moral monster are common criticism of Calvinism, ones with which I agree.

In his book The Human Faces of God Thom Stark shows how some views of God in the Bible are morally and practically problematic. Commenting on 1 Kings 22:19-23 , where God is said to intentionally send deceiving spirits, and Ezekiel 20:25-26, where Ezekiel claims that God himself gave evil commandments to the Israelites as punishment, calling them to sacrifice their own children, Stark observes that:

If Yahweh’s sovereignty entails the use of evil means to accomplish his undisclosed objectives, if Yahweh sent lying spirits in order to deceive, if Yahweh intentionally commanded the Israelites to sacrifice their children in order to punish them, if he intentionally gave them bad commands (at least one of which we know to be recorded in Exodus 22, where it is depicted deceptively as a good command), then what is to prevent God from intentionally giving us other bad scriptures, intentionally obfuscating revelation as a form of punishment, or some sort of examination, to test our mettle? (Stark, 2011, p. 66).

In a later chapter Stark critiques traditionalist attempts to defend the moral rightness of texts calling the Israelites to genocide. After quoting one such apologist as saying that goodness is defined solely by God’s actions, and if God chooses to act differently today than yesterday, then goodness today is different than it was yesterday, Stark observes that,

In this picture of God, there is no consistent character. If God has no consistent character, then God’s self-revelation would be meaningless, because anything we learn about God could potentially be contradicted the moment God chose to be otherwise. Moreover to say that God is good when God does precisely what God has told us is evil is to render the language of good and evil meaningless (Stark, 2011, pp. 136-137).

I agree with these authors and others that God’s goodness must be at least analogous to what we everywhere else mean by “good” or it becomes meaningless and unrecognizable. That leads to a practical volunteerism. I believe it involves an equivocation with the word “good.” As Stark particularly shows, it undercuts our ability to trust God. And not only would it undermine our ability to trust specific messages, it leads to uncertainty about God’s actual, enduring benevolence toward us.

Many of us would find it impossible to sincerely worship such a God. We could go through the motions, but we could not truly love or adore such a being. Finally, such a view opens the door to heinous deeds being justified as God’s will. Or to put it negatively, we would have no firm basis for ruling out heinous deeds as possibly being commanded by God.

Conclusion

In my next post I will share a personal and complementary reflection on pragmatic reasons for presuming that God is good in a way that is for us and analogous to what goodness elsewhere means to us. Doing so will help clarify the arguments from this post and also anticipate some common objections to my approach.

References

Armstrong, K. (2015). Fields of blood: Religion and the history of violence. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Armstrong, K. (2006). The great transformation: The beginning of our religious traditions. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Baggett, D. & Walls, J. L. (2011). Good god: The theistic foundations of morality. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

de Waal, F. (2008). “Getting Along” In The altruism reader: Selections from writings on love, religion, and science. pp. 242-262. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press.

Hick, J. (2005) An interpretation of religion: Human responses to the transcendent (2cd Ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hvidt, N. C. (2011). “Patient belief in miraculous healing: Positive or negative coping resource?” In The cambridge companion to miracles. Ed. Graham H. Twelftree. pp. 309-329. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Jennings, T. R. (2013). The god shaped brain: How changing your view of god transforms your life. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books.

Keller, T. (2008). The reason for god: Belief in an age of skepticism. New York, NY: Dutton.

Lee, M. T., Poloma, M. M., and Post, S. G. (2013). The heart of religion: Spiritual empowerment, benevolence, and the experience of god’s love. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

McLaren, B. (2013). “Forward” In The jesus driven life: Reconnecting humanity with jesus (2cd Ed.). Michael Hardin. pp. xiii-xvii. Lancaster, PA: JDL Press.

Newberg, A. and Waldman, M. R. (2009). How god changes your brain: Breakthrough findings from a leading neuroscientist. New York, NY: Ballantine Books Trade Paperback.

Pinker, S. (2011). The better angels of our nature: Why violence has declined. New York, NY: Viking.

Reitan, E. (2009). Is god a delusion: A reply to religion’s cultured despisers. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Smith, D. W. and Burr, E. G. (2007). Understanding world religions: A roadmap for justice and peace. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Stark, T. (2011). The human faces of god: What scripture reveals when it gets god wrong (and why inerrancy tries to hide it). Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock.

Witte, J. and Green, M. C. (2012). Religion and human rights: An introduction. New York, NY; Oxford University Press.

I have five core commitments that inform all of my other beliefs and the way I aspire to live. I see these beliefs as interconnected and mutually reinforcing. But they are also separable and I hold inner commitments more firmly than outer ones. In that sense, they are like castle walls within castle walls that ripple out from a sacred center.

I have five core commitments that inform all of my other beliefs and the way I aspire to live. I see these beliefs as interconnected and mutually reinforcing. But they are also separable and I hold inner commitments more firmly than outer ones. In that sense, they are like castle walls within castle walls that ripple out from a sacred center.